There was a time when Jimmy Buffett1’s song “A Pirate Looks At Forty2” seemed to me like a nostalgic song from the POV of a time-wisened, rum-marinated geriatric pirate winding down a long life, ruefully reflecting with mild melancholy3 on how it all panned out. But I passed the 40 milestone quite some time (fine, years) ago and now it seems insane to me that I ever thought 40 was old, much less that there would be any “panning out” by now. Perspective, huh? But, yeah, I currently find myself creeping up on (skidding? lurching? stumbling? towards) 50.

FIFTY?!?

So…my personalized version of Jimmy Buffett’s song would be “A Musician Looks At (stares down? plays chicken with? stumbles towards) Fifty.”

Not quite fifty, here I am, still writing songs like a deeply inspired snail, still doing the logistical algebra to schedule band practice, still throwing my back out lugging around guitars and amps and lyric books, still creating rough-but-close-enough chord charts for the band, still writing and rewriting setlists, still sending non-AI-written bottomless follow-up emails & texts to promoters and venues and journalists and my own loyal email list, still playing shows and festivals and all that. Not because I believe there’s some constellationally-fated, karmically-due big break awaiting me. I’ve disabused myself of the notion that some vaunted gatekeeper’s gonna discover my music and suddenly pluck me from obscurity, shine their glowing & universally respected floodlight on little ol’ underappreciated me, and put me & my songs on the map (and the fourth line of the Outside Lands Festival poster). I’m not holding my breath for a Grammy. Or even a sold-out show in a cozy venue, really.

It’s not the first time I’ve had to stop to consider why I do it4. In my most self-pitying hours, that probing question comes out sounding like a discouraged, exasperated “what’s the (expletive) point?”5 Yet in my clearer and freer and truer moments, the question becomes more curious, like “what is it about music that keeps me coming back to writing and performing it?” Let’s run with that one today. And for the sake of universality and accessibility, let’s tweak it ever-so-slightly to “what is it about creativity that keeps creators coming back?” That way, maybe this is centimetrically6 less navel-gazing and more adaptable to whatever creative endeavor—painting, woodcarving, cooking, parenting, needlework, poetry, bookkeeping, fashion, etc—you might connect with.

It goes without saying that the act of creation alone provides a massive net-positive impact7 on my life that only it can—from being spiritually fulfilling to boosting (some days) my self-esteem and mental health, as well as better understanding myself (and sometimes the world) and just the pure joy of creation or the unmistakable catharsis of expression. That’s where it all starts.

Creation, however, is not the whole picture. For whatever reason, I also feel compelled to play the songs for people. Ideally listening people. To share it. To connect with others through the songs, in the songs. It really would be so much simpler if 100% of the fulfillment came solely from the creation, just a quirky mad scientist happy as a clam to be splashing beakers around in the basement.

Alas, that’s not how it works.

A funny/unfunny thing happens as you make music and play shows. This thing, it can mess with your head. When you’re younger, like in college, it’s no herculean challenge to get people to come out to shows. It feels hard and you worry about it, but it’s not that hard. You’re single. Your friends are single. You’re part of a community of untethered single people, all of whom have friends in other circles of untethered single people, many of whom could easily be talked into showing up at your show for a measly $5. If you rally just a little bit, hustle and mobilize, your show can turn into The Thing People Do on some given weekend night. There’s some buzz. Possibility ripples in the air. Even if they’re not there explicitly for your music, you can attract a respectable crowd8, fill the room. And, suddenly, it can feel like you’re onto something, should you decide to take credit for the turnout9. It can feel like momentum. Sometimes it is. And sometimes, it’s more a by-product of that untetheredly single stage of life.

If you stick with it, you’re likely to get better at it, both the songwriting and the performing part. But, unless you’re a dyed-in-the-wool go-getter and self-promoter and self-marketing whiz and are able to summit the e’er-daunting Mount Fans That I Don’t Know Personally10 and find yourself on the winning end of some lucky breaks11, over time, the audience kinda naturally shrinks (see footnote 5 ). Or at least that’s what it did for me and a statistically significant12 chunk of my fellow musicians. Friends start having kids. Their nights are spoken for. Budgets tighten up. The kids start having recitals and soccer games and art classes and Wax Museum Night at the school. Your friends are exhausted. They’re not leaving the house for the Resurrected Beatles, much less their buddy from college’s sad-sack songs13. And you, the musician, don’t take it personally, at all. You can’t. Because you get it. You are also exhausted (plus, see footnote 13’s comment about tennis). The difference is that you are inwardly, involuntarily compelled to create/perform anyway. It matters to you. It even feels like oxygen sometimes in its utter necessity.

So you keep going.

We toyed. No, toyed sounds trivial. We seriously considered moving to Nashville for a few years, visiting a number of times, interviewing for several jobs and being offered one really fun position at an ad agency, even looking at houses in a few different neighborhoods with a real-deal licensed realtor.

Was the draw of Nashville that I would “hit it big” by being there in the country music capital of the world? No. Not at all. I will cop to the fact that substantially more opportunity exists there, sure. Duh. You are far more likely to catch a fish when you’re in the river (or near water, for that matter). No question. But it was less about striking gold than it was about fundamental way of life.

As I’ve mentioned too much already, I’m nearing 50, which is ancient to my kids but doesn’t feel that way to me14. And, as I’ve also mentioned a lot, I want (need?) to keep playing music, writing it, playing it for people, making connections with other musicians. But, in a place like Salt Lake City15, you’re apt to run into (stumble towards?) a couple things:

for obvious reasons, the majority of music venues are college-type venues, where the music and audience skews young. I’m lucky that the owners of The State Room (which skews markedly older) and Velour will still book me and my band, but I also realize that 40somethings without a hit song16 aren’t exactly their ideal, audience-magnetic booking target. At what point are they gonna see me as too old to play their venues (especially when I’m not exactly filling the room in the first place)?

in everyday conversation with people, at work or around the neighborhood or in the bleachers at the football game or in the halls at church, there’s a tone that sneaks in whenever someone asks those few loaded words, “you still playing in your (little) band?” The optional parenthetical diminutive there is the thing that cuts the most, but even without an overt “little”, it’s implied and the question usually has an undertone of “haven’t you outgrown that yet?” or “does this guy think the world is suddenly gonna go crazy for a 50-year old songwriter?” or “how does Holly put up with this guy?” It’s not intentional or mean-spirited, usually. But it’s in there.

Both of those bullets signal that, at some point, a musician can (and should) “age out.” That music-making is a thing that one would “hang up.” Nobody asks a painter or photographer or chef if they maybe ought to hang it up. Those strands of art don’t fetishize/favor youth nearly as much. If anything, they seem to value the long game, the craft that can only be developed with concentrated and voluminous time, focus, dedication. Look at sushi chef Jiro Ono, subject of the wonderful documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi, who kept making (and evolving) sushi until just two years ago at the age of 98!17 People mourned the day Ono decided to stop making sushi. Yet with music, for whatever reason, you’re suddenly like a pitcher too old to play little league or a quarterback who’s run out of NCAA eligibility? There’s no more runway? The road just….ends? (Or should, depending on who you’re talking to.)

So one of the attractive aspects of relocating to Nashville was, while there is certainly a slice of that town that is image- and youth-obsessed between fillers and hair extensions and boob jobs and spray tans and all that, there is a purer music-loving—no, music-living—slice where music-making is a lifestyle. A way to live. An inextricable element of your very humanity.

I sat at The Station Inn one night in Nashville, no more than 9 feet away from songwriting legend Guy Clark who was putting on a masterclass18 . The room was pin drop quiet, save for when it was filled with waves of applause or eruptions of laughter triggered by his witty asides. Clark was in his early 70s at that point, all character wrinkles and jowls and sly surl. Yeah, he wasn’t gonna be featured on the CMAs alongside all those flat-ironed truck bros in their bedazzled jeans singing about tailgates and red Solo cups. But who cares? Music, not fame and not commercial adulation19, was Clark’s path, his way of life.

Hearing Clark play his song “The Cape” that night, my jaw dropped to the floor at his gift and craft. I suspect it was the equivalent of eating a transcendent piece of Jiro Ono’s sushi. It was everything I could ever want in a musical moment, the intersection of storytelling and music and performance.

The real epiphany, though, was this:

Nobody’s asking Guy Clark “are you still playing with your (little) band?” To the contrary, people were hoping he’d keep playing and writing and playing again forever. At the spry age of 72, far from his purported “prime”, Clark released one of his best songs, “My Favorite Picture of You.”20 Similarly, nobody ever asked John Prine if he wasn’t maybe a little old to still be writing songs. No, we all just loved that he gave us The Tree of Forgiveness21 before he died. And mourned that Covid took him way too young at 73. So many artists, musicians and otherwise, have created vital work long after their pop culture expiration date.

The draw of Nashville, besides residing in the music world’s proverbial river, was the beauty of never aging out, of music as a lifestyle, that it felt like an outlier in a world and industry that otherwise fetishizes/worships youth, that’ll spit you out at the mere suggestion of your first wrinkle, that can declare you an obsolete has-been (or never-were) before your mid-20s. But that’s the industry, not the music. The music isn’t done with us…ever. A subset of Nashville seems to understand that.

Music, as a lifestyle, is just what you do. Or, maybe put it this way, music as a lifestyle is a way of being.

That was what I was looking—and still look—for.

SPOILER: we never moved to Nashville. We agonized over it. And we had some inarguable, solid reasons and inspiration to stay in Utah. Still, I was deeply depressed22 after hanging up the phone with the Nashville ad agency I’d been actively courting for 2-3 years, telling them “no, I actually won’t be taking the dream job you finally offered me.” See, there are myriad dreams. It’s complicated. You know the proverb about how there are two wolves inside of you, always fighting? Maybe it’s like that. Or maybe it’s like a wolf-related Tom Waits quote, “Family and career don’t like each other. One is always trying to eat the other. You’re always trying to find balance. But one is really useless without the other. What you really want is a sink and a faucet. That’s the ideal.”

In search of that sink and faucet, we stayed in Utah.

Ultimately, I dusted myself off and decided life is what you make it. Or, maybe put it this way, life is music so make it23.

Sliding doors. No, I’m not writing songs for Miranda Lambert or singing harmony with Kasey Musgraves or co-writing songs with my dream co-writer Lori McKenna, but I’m still going, trying in my own way to forge a life in music, to keep making music with my (little) band. That means shows that I worry no one will come to and shows that I really hope people don’t miss24 (those are different feelings, trust me; one has fear at its core and the other has radically high self-belief there). It means being the oldest band at the local music festival. Means singing at funerals and weddings, living rooms and hospital rooms, chapels and classrooms. It means the lonely, solitary act of writing late into the wee hours as well as the vulnerable, brazen act of sharing what I’ve written. It means the occasional co-write for strength in numbers, for a witness, for a step outside my own overactive brain. It means tribute shows to build community, shows with The Lower Lights to nurture community, going to new (or new to me) bands’ shows to expand community. It means showing up for my community, whether that’s the occasional cherished sideman gig or recording session or just going to my friends/peers’ shows or rallying for their latest Kickstarter campaign or even just texting them when I happen to listen to one of their songs to remind them how meaningful their music to me. It means mumbling a Voice Note into my phone at 2am or in the stairwell at work or on my morning commute so I don’t forget the light bulb that just fired up an idea for a song or lyric or arrangement. And it means trying to save up enough money to make another album25, even though hardly anybody buys albums (which would feel less discouraging if my streaming numbers rose) or thinks about albums (which would feel better if I were getting playlisted by the tastemakers) anymore. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg of what it means.

It may not look like what I thought Nashville would be. Heck, Nashville likely wouldn’t have been the romanticized diorama Camelot I’d concocted in my head. Honestly, all that stuff above? It….kinda sounds like…music as a way of being, Nashville or not.

I should disclose: I am very much NOT a Jimmy Buffett (RIP) fan. I mean, I don’t drink and I don’t even really “party” per se and I certainly don’t go for calypso-adjacent Gulf & Western kinds of music. I’m perfectly satisfied with the current low amount of steel drums in my life, is what I guess I’m saying.

I saw Jimmy Buffett in concert once, not against my will but not voluntarily either, as part of Neil Young’s Bridge School Benefit concert. As the show went on and we inched closer to Buffett’s set, I leaned over to my left to Holly and our friends the Wheelers and sniped, probably too loud, “I don’t know what I’m dreading more: Jimmy Buffett or his fans.”

They laughed. I laughed. The show went on.

The next act was Buffett. And the second he took the stage, the stranger to my right immediately got to his feet, threw off his plain, unassuming-looking jacket to reveal an obscenely tropical Jimmy Buffett shirt. He was losing his mind, clapping up a storm. Doing a very stiff, very confusing, very caucasian motion with his hips. Full-on Parrot Head.

I was 1) impressed with his confidence and enthusiasm and commitment, 2) feeling bad that I had been so derogatory and likely offended him (or made him hate me if heard me), and 3) still wondering whether the fans or Buffett’s songs were more aggravating.

If I had to pick, the two Jimmy Buffett songs I can stomach:

Come Monday (because I’m sucker for ballads and a girlfriend once put it on a mixtape for me so it has teenage sentimental value)

and

A Pirate Looks At Forty (I had it mixed up with “Son of Son Of A Sailor” but I just listened to that one and, um, no.)

I had a couple friends who loved “Cheeseburger in Paradise”, “Margaritaville” and, yes, “Why Don’t We Get Drunk.” We were driving cross-country once in an old Land Cruiser and, back in the pre-streaming era of compact discs, we’d take turns picking the music. And once in awhile they’d put on Buffett’s greatest hits and I would…endure.

None of it is my jam. To each their own.

saudade? ennui?

I realize that this goes hand-in-hand with previous post(s) that touched on Why Do I Write A Substack. That’s how the overthinker/navel-gazer life goes. Like I said in another overthinking, Billy-Collins-referencing post, we circle ideas, come back to them, rephrase them, look at them from another angle. It’s why someone like Bob Dylan can spend half a century writing songs about heartache. Like it or not, he circles back. Not all of them are profound. But some of them sure are.

On my lowest days, if you were wondering and want to venture down the befanged rabbit hole with me, I am literally haunted by a harrowing-to-me story found in Speaking with the Angel, a charity anthology of short stories that author Nick Hornby (High Fidelity, About A Boy) compiled.

“Harrowing?” you wonder. Your mind might immediately leap to gore and guts, Blood Meridian stuff. Or abuse or violence or creepitude or starvation or poverty. Nope, this is not that. No blood. No guts. No creepitude. Plenty of facepaint, though. (Not clowns, though, don’t worry.)

Written by British author/scriptwriter/comedian/political campaigner John O’Farrell, the short story Walking into the Wind goes a little like this:

Man is a mime. An ascendant mime, making a name for himself. In his 20s, his friends enthusiastically attend his gigs, marveling at how cool it is that he is an actual performer on a side stage at the legendary British festival Glastonbury! They’re all loving the youthful party energy of it all, in awe of his cool, artistic, bohemian lifestyle. Maybe even envious! Man lives and dies for it, feels it to be his personal mission, believing mime to be the purest, best way to express the human condition.

His friends, though, soon grow bored of it, after going to the umpteenth hard-to-find small theater performance, realizing most of his routines are pretty similar if they’re even distinguishable at all. His friends get married, work lucrative jobs, start families, enjoy their wealth, stop coming to his performances. Man also becomes a father, which only puts more pressure—internal and external—on him to become a successful mime and make more money. Some of the story’s underlying comedy is found in the fact that, for most of us, it would be impossible to name even ONE successful mime. What would be the crowning achievement for a mime? What is the Mime equivalent of an Oscar? You can see where this is going.

And then comes the harrowing part: years (maybe decades) later, Man’s still going at it, a thoroughly mid-level mime, and again performing on the kinda-hard-to-find Mime Stage at a festival. His friends rally one last time, for old time’s sake, and show up to see him doing what, to any outsider, seems like the same routine he’s always done but what, to him, is the most important piece he’s ever performed: staging his own life IN MIME. His magnum opus. With years of perspective, the friends see that the shine has worn off of what they once admired (maybe even envied). They feel intense Fremdschämen, vicarious embarrassment and bits of shame for how pathetic his (little) miming life is.

“Why would that be harrowing, Paul?”

Well, all you’ve gotta do is swap out “mime” and swap in “music” and you can see why someone in my position, on the wrong day, might feel a little rattled by how much they relate to Man.

Oof.

not a word

How sad is it to even write a sentence like that about creativity? Something that should just be allowed to be. Not burdened by efficiencies or metrics or outcomes or ROI. Yet here I am, justifying with outcomes/results. At least my justifications are not just based on money or “likes”? Just creating should be reason enough!

As I’ve written before, one of my first New York City shows was at the legendary CBGB’s. I had the 8pm slot, I believe. And I had a stellar turnout—one I would kill for today—of around 90 people. A lot of them came from the local Mormon singles congregations, a handful came from my day job in the advertising industry. Most of them had probably never heard my songs before (and most have probably not heard them since), but they all came together because: why not? “I’ve never been to CBGB’s.” “I heard (attractive male) is going to be there.” “Maybe (attractive female) is going.” “I could really use a drink.” “What else are we gonna do?” Even “I’ll feel bad if we don’t go.”

As long as you’re willing to also take the blame when the turnout’s a little disappointing.

I was not. And that’s…ok.

it doesn’t hurt to be freakishly good-looking.

A big reason why I have so much respect for the music careers carved out by friends like Peter Breinholt (who had DECADES of turnover in his audience and still played really big and impressive shows) and Book On Tape Worm (still selling out their annual Slumber Party shows) and Mindy Gledhill (who has evolved relentlessly and basically Ship of Theseus’ed her fanbase while still drawing a serious crowd), among others.

Nick Paumgarten, in a recent article about a Met Museum exhibit featuring guitars, wrote:

There’s another kind of guitar guy: he played growing up, and now, in middle age, ramps it up again and goes down the hole. Pandemic, empty nest, dwindling appetite for new friends and maybe even for the old ones, too. The guitar, like golf, invites solipsistic dissolution masquerading as self-actualization. Or perhaps it’s the other way around. See the weekender in his basement, wearing pressed khakis and a Montauk hoodie, with his new Stevie Ray Vaughan Strat and his Fender Twin Reverb amp, working out the riffs in “Voodoo Chile” or “Midnight Rambler.” Or else hunched over his phone, spamming friends with audio selfies and guilt-inducing invitations to his Friday-night dad-band bar set. I have a lot of friends who will take this description personally. I don’t ask them to watch me play tennis.

OUCH.

…said every 50 year old ever

a place I love, knowing all (or most of) its asterisks

(Pardon the language.)

Tift Merritt wrote a beautiful and heart-rending Substack post that runs a bit parallel to mine in terms of “the industry vs the art” and really nails the “hit” thing.

You could argue, “but he was a genius.” Which is true, by all accounts. But do you have to be a certified genius in order for your art to matter? And to continue mattering? And to matter to whom? And does art even have to objectively “matter” to be worth making?

Lots of questions.

not an actual class. a concert.

It’s worth pointing out that Clark was playing The Station Inn, which has a capacity of 175 people, not Bridgestone Arena across town, which could fit 20,000 fans.

Which is saying something for a guy who wrote deceptively plain-spoken all-timers like:

Desperadoes Waiting On A Train

L.A. Freeway

Dublin Blues

Homegrown Tomatoes

Out In The Parking Lot

The Guitar

Anyhow, I Love You

Same with Bowie and Blackstar, Leonard Cohen and You Want It Darker, Warren Zevon’s The Wind, and Johnny Cash’s American Recordings IV. All of them showed artists who still had something to say and an artful way of saying it.

more deeply depressed? lol. This was long before I got myself on any kind of decent regulating medicine.

Too pithy? I dunno, I kinda like it.

Is this a bad time to pimp my upcoming mime performance? Is it manipulative to drop my heartfelt “it’s hard but it’s worth it” post on you and then post a link to a mime performance concert happening THIS WEEKEND?

Maybe. But here’s a ticketing link for you to see a lineup of artists unlike any I’ve ever been a part of (to say nothing of the entire amazing Saturday bill).

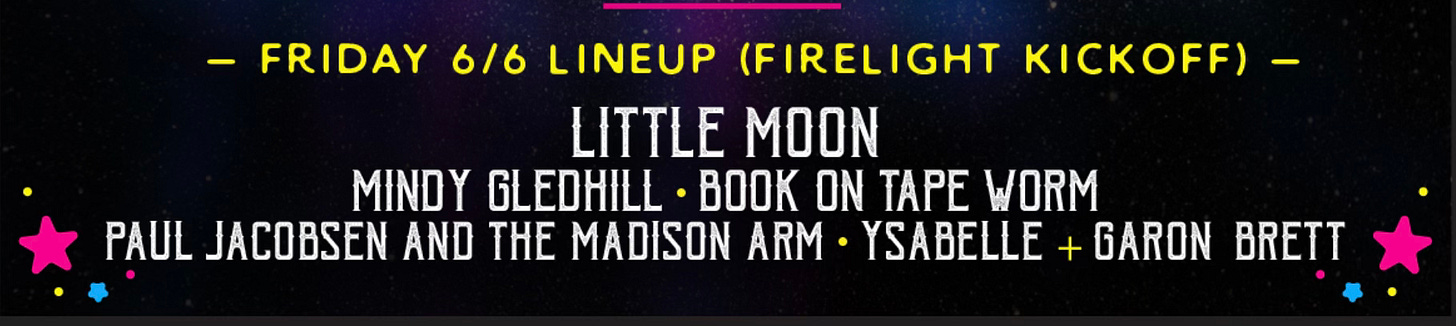

I put this little shill in the footnotes to feel less gross about it. But, for the record, file this show under the I Really Hope People Don’t Miss It banner. I’ve got some radically high self-belief, for once—the band is sounding unreal and you would leave happy if you only got to hear any ONE of the other artists: Little Moon (featured on NPR’s Tiny Desk!), Mindy Gledhill (I don’t even have to tell you about Mindy, you already know), Book on Tape Worm (known to make grown men [me] cry and inspire bona fide chills), and Ysabelle (a viral YouTube sensation, and I don’t mean that hyperbolically) & Garon Brett (one of the best-kept secret musicians in the Utah music scene).

End of shameless plug.

I hear bands, often past their prime (how dare I say such a judgmental thing in an essay that’s decrying ageism? see how prevalent and second-nature and deeply embedded it is?), talking about their new album as The Best Thing We’ve Ever Done. And then I listen to the actual album and roll my eyes (respectfully!) at their qualitative delusion. Randy Newman has an amusing, incisive song about this called “I’m Dead But I Don’t Know It.” (See Footnote 5) And then the choking irony is: I find myself feeling just like they do, that I am sitting on some of the best, most interesting work I’ve ever done. I suppose my argument for being an exception is that, unlike Counting Crows or the Pixies, I never had to reckon with a commercial peak or cultural oversaturation or the pitfalls of celebrity. But still…

beautiful