The Guy's Purple Coat Was Cool

It would’ve been 2004, I think. I was decompressing on the beat-up futon in front of the beat-up tv in my Chinatown/SoHo apartment. My flip-phone1 buzzed. It was a text from my brother Andy.

“i think i just saw your commercial. not really sure what happened but the guy’s purple coat was cool.”

That second part—“not really sure what happened but the guy’s purple coat was cool”—is in the running for the title of my life-in-advertising memoirs2, should I ever write them. It could sum up my career as a creative in a lot of ways we won’t cover here today.

Purple Coat Guy (not the actual title of the ad) was a big deal for me: the very first tv commercial of my advertising career. It was a big deal for the client too, who paid in the neighborhood of $1.3 million for the thing. A small price to pay for my brother’s takeaway being (and Andy was far more inclined to attempt to really “get” it than the average Thursday Night tv viewer whose brother had not written the ad) the guy3’s purple coat.

Success!

Months earlier, my partner David4 and I had been roped into a big pitch with what felt like the entire creative floor. The creative directors wanted a flood of ideas. This notoriously finicky client hadn’t signed off on a tv commercial for a whole year—a troublingly long time in that era. Red lights were proverbially flashing. Account directors were losing their minds (and, soon, jobs). That meant it was all hands on deck. Time to 1) bring in some fresh blood, and 2) empty the clip.

The creative brief’s big takeaway for the commercial was supposed to be: The new [BRAND REDACTED] mobile phone can do all these amazing things—video, photo, and it PLAYS MUSIC!

We take all those features as automatic now. Table stakes, so to speak. They’re not even….features anymore.

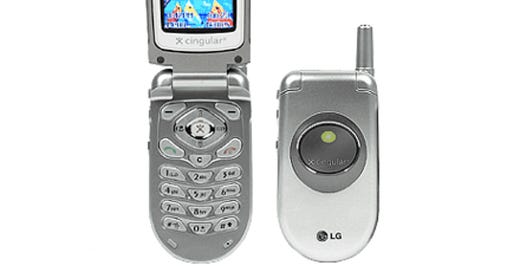

Remember, though, twenty years ago, mobile phones were still mostly like this:

And, if you wanted to send a text message, a lot of people were still forced to text neanderthalically5 like this:

666 555 3 / 7 44 666 66 33 7777 / 7777 88 222 55 33 36

It’s hard to explain to someone today (my kids, some coworkers, the unfortunate bezitted7 teen bagging my groceries) how novel a phone with photo (gasp!), video (double gasp!), and music-playing capability (all the gasps!) was at the time. There were no iPhones yet. Blackberries still roamed the hillsides like chunky ankylosauruses8. Photo and video were rare and, even when phones had them, the quality was lousy.

So, yeah, the creative brief’s takeaway was: everything in one place! How many times in my career have I been asked to cook up a new way to say “all-in-one” or “everything in one place”9 or, worse, “the best”? This was my first job out of college and I’d already worked a number of creative briefs like this at both my internships. It’s a very common benefit that I assume it performs well in focus groups10, though I haven’t seen the numbers.

Anyway, David & I pitch a few concepts. So do other teams. One of ours defies the odds of our inexperience and becomes a finalist, to everyone’s surprise including ours. We make some tweaks. Repitch. Tweak. Repitch.

And then, somehow, I don’t know, the client11 picks our concept over a bunch of other, more-senior teams with what idea exactly?

This idea:

Our protagonist boards a bullet train and picks up this special new12 [BRAND REDACTED] phone which turns his reality into a, for lack of better word, surreality. As he makes his way through the train, each train car represents a different feature of the phone. So….the first car is giant metaphor for photographic capability. The next car: video. And the last one has a live band playing (the same song as is playing in the background of the entire commercial). The phone has it all. Photo, video, music. The end13.

Correction: photo, video, music + purple coat, the end.

I’m still stunned that Hollywood didn’t come calling. It’s not that far off from the premise of movies like Snowpiercer and Train To Busan and basically any number of 2D Nintendo games from the 20th century. A multi-phase hero’s journey of magic and discovery (and cellphone features!). Not groundbreaking. But we were selling phones, not fishing for Oscars.

So we were off. To where? First Prague14, then Berlin, then Frankfurt, then back to Prague. Not a bad life, all in all.

The local driver who picked us up at the Prague airport took no more than three sentences to offer to take us to the local brothels. Clearly, he had worked with ad agencies before15…

We skipped the brothels and met up with our creative director/boss Greg, a gentleman among scoundrels and his friend, a more-senior freelancer16 (see also: insurance policy against young/inexperienced us) named Nate17. (“These guys are gree-een,” he said to Greg without trying to be subtle when we arrived. I took it ultra-personally while also completely agreeing.)

We all met up with the production company, who had done work for movies like Van Helsing, which wasn’t the most prestigious thing ever but trumped the crew I worked with on my student video at BYU by miles. After weeks of phone calls and preproduction, we finally met face-to-face with our director, Antony Hoffman and his team.

Antony was well-regarded in the ad world18—some cinematic flair, a worldliness, and just enough edge that you didn’t want to tangle too much with him. A native South African, he was the definition of professional—savvy, quick-witted, solution-driven, maybe just a little pretentious. He showed kindness in how he dealt with the inexperience dripping off of me and David. I’m sure he rolled his eyes when we weren’t around, but generally treated us like equals, which meant a lots, even if we knew it wasn’t true. We found out he had directed the sci-fi movie Red Planet (with star Val Kilmer, who was not spoken of glowingly) and that the production was such a mess that he threatened to quit various times only to be coldly told he’d never work in Hollywood again if he walked out. Antony, leaning on his personal pride in his work (and some strong, expensive wine), finished the film. And he still never worked in Hollywood again. The movie was an $80 million flop. Brutal.

We jetted off and spent a day and a half (which was not nearly enough time) in Berlin just for casting. Casting is a really discombobulating experience in which you—an admitted mortal—find yourself nitpicking the appearance of really, really attractive people. People who, if you saw them on the street, would almost surely be the most attractive person you saw that day. But they come in to the little audition room in a giant cattle call, one after the other, and pretty soon you—again, an admitted and schlubby mortal—become out of touch with reality, desensitized to the objectively good-looking-ness of all of them. The things people say, after the auditioners have left, in these rooms? Absurd. “Hmmm… I dunno, her nose is, like….too nose-y.” Or stuff like “is he too good-looking? We need someone believable.” Or “his ears were a little (makes hand motion).” It’s so stupid. The experience is adjacent to the philosophy that every Olympic event should start with a mere mortal attempting the event (javelin, bobsled, ski jump) just to show the degree of difficulty: all casting sessions should require the selection committee to take a selfie with each of the people they reject. These genetically-blessed, objectively attractive casting hopefuls are the deep-sleeping wolves in the old adage “wolves do not lose sleep over the opinion of sheep.” The scruffy American ad dudes, slumped on the couch, clutching their Diet Cokes? We were the sheep. Bahhh.

(And that’s not even getting to their actual acting ability, which is a whole other level.)

From Berlin, it was onto Frankfurt, which was terminally boring. No offense, frankfurters, but your city had nothing for me in 2004. We missed a Van Morrison concert by a day. We did some walking. We just did a ton of location scouting—which sounds exciting when you’re working on, say, Lake Como or the Swiss Alps or pristine Caribbean beaches. Our location-scouting was mostly driving around the less-developed edges outside of Frankfurt, looking for picturesque places where the bullet train drove past so we could get exterior shots. Oh, the glamour.

“You have no (expletive) backbone, man! You’re just (expletive) folding whenever the client wants anything!”

David was yelling at me on some street corner in downtown Frankfurt19. German people were noticing the Chinese guy shouting spiritedly in English at the tall redhead. I was flustered and, as I am prone to doing, was getting VERY insular, which was creating a boiling kettle effect with my insides. Steam. Bubbles. Agitation. Fury.

Ironically, considering my life’s curriculum vitae, our argument was over the music we were using for the commercial. We’d been hunting for weeks for just the right song. In addition to that, we’d also been trying to find an artist where it might be of mutual benefit—we boost some single they’re hoping becomes ubiquitous; they give our phone commercial a cool soundtrack. A common strategy to this day. Think how Jet’s “Are You Gonna Be My Girl” utterly exploded when it was featured in an iPod commercial. That was the idea. Synergy, as the account folks would say.

Anyway, we had pitched our idea to a bunch of different bands. Most weren’t interested. Either the money wasn’t enough, the product wasn’t cool enough, or they were still part of the deeply embedded No Sellout culture that was pervasive in the 90s and well into the early 00s20. We were really close to getting British rapper The Streets, who definitely had a higher ceiling21 as far as street credit and viralability22 were concerned.

Our argument took place after we learned The Streets had declined our offer. We were literally already shooting the commercial and didn’t even have a band on board yet. There were a lot of feelings. I had probably become too pragmatic and was bending, figuring we had exhausted our resources to get something we wanted and—time breathing down our necks—now was the time to figure how to make something (anything!) work. In my eyes, I was being pragmatic about the timing and the budget (meaning: it was limited and we weren’t gonna get The Strokes or The Stones). David was upset by what he perceived to be my surrender and compromise of our vision, which—if it lacked nuance of the situation—wasn’t untrue.

Our argument introduced a theme that would recur throughout my career: working with an unbelievably talented & hard-nosed art director, and my pleaser side being a source of tension. It—the push and pull between me wanting to get the job done and make clients/employers happy, and my incredibly talented partners wanting to keep their artistic integrity intact—would happen over and over in my career and, here, David was accusing me of rolling over. He wasn’t wrong—being creative and a pleaser is a juggling act I don’t always excel at. I have caved when I shouldn’t have. But I have also stood up when it seemed the right time. And I’ve helped keep things going by picking battles, sometimes well, sometimes poorly. Either way, his staunch (accusatory) stance wasn’t winning battles—with me, with the agency team, with the client—either. Neither of our methods had successfully found the right band. Our inexperience (particularly our inability to transcend or ascend above our inexperience) was taking its toll in the form of anxieties that came out as barbs and lashes. We were cracking. He let me have it. Eventually I yelled back. Laundry was aired. Swear words volleyed. Cruel steam was vented. One of us stormed off.

Techno house duo Swayzak from the UK accepted our offer the next day. We finally had a song23 (though not one quite as catchy nor destined for the bigtime as The Streets’ song). We had a band. Well, sort of. Swayzak is an electronic duo, which usually means Two Guys On Laptops. For our ad, the two main guys pretended to be playing a keyboard and a bass. I just now remembered that The Guy In The Purple Suit wasn’t even in Swayzak. He was a guest singer (much like Massive Attack or Moby or Daft Punk use special guests). And he got the purple suit, lucky guy.

Steam gone, grievances aired, music secured, David and I met up and got a doner at a local Frankfurt food truck and all was fine. This was when I realized that a decent bite to eat could sometimes salvage a crappy day/situation. Food therapy (or food coping, more accurately). We may have even hugged it out. Besides being a stellar creative mind, David was really good at forgiveness, at making sure the water was truly under the bridge. He’d burn it off and be done with it. I still struggle with holding onto things.

We bounced back to Prague, where our production company had rented out an old abandoned hockey rink that was situated on an also-old, also-abandoned fairground-type site. Why a hockey rink? Well, first off: cost. But second: it was big enough to build big things in there.

Like what?

Like a set of three life-sized railcars.

See, we didn’t actually film in a real train (too expensive, too many variables, not enough control). We had a crew that built models of the interiors of train cars that we could shoot in. The windows were covered in green material so that we could later make it look real with the passing landscape we had shot during our time in beautiful Frankfurt.

After long days in the hockey arena, we’d go home to our little hotel called the Aria, where each room was named after different musicians/composers. Mine was Louis Armstrong. Every morning I would wake up and look out the window to see this:

Not on the weird, stretched angle shown here. But, still, a pretty amazing view from my window.

Some mornings I’d head down to breakfast and run into the great character actor Seymour Cassel, who charmed everyone and, I think, was surprised to be recognized at all24. You know I can’t resist a namedrop, especially if he’s been in a bunch of my favorite movies and the guy once enthusiastically greeted me as I entered the dining room.

A week or so later, shooting was over. We had a wrap dinner at the foot of the famous Charles Bridge and were on flights home the next morning.

It was our first shoot. So when the director and our creative director and the client were all happy with what we’d done in Europe, we believed them.

Back home in NYC, we found ourselves for a couple of weeks down in SoHo, cutting together our commercial with none other than Hank Corwin25. At the time, he was best known as Oliver Stone’s go-to editor. But he would soon edit movies for one of my favorite directors, Terrence Malick. Little did I know that it wasn’t gonna get much bigger than this for me.

Hank was a sweet guy, patient with us. He was my first chance to try out the advice a more senior creative had given me: “You’ll have a lot of ideas for edits. My advice is to wait until you’ve had 6-7 ideas and then just, carefully, propose ONE of them.” I use that advice to this day, most of the time.

We were ordering lunch one day and Hank taught us the NYC-ism “No sushi on Mondays.” The logic: restaurants over-order for the weekend and then typically use no-longer-fresh fish on Mondays. We were just excited for the free lunch and wanted to capitalize with some sushi. Hank taught us some nuance. Some patience. We got salads.

As for the work…

Imagine: an editor who can make Oliver Stone and Terrence Malick movies feel cohesive, but was at a loss for how to make Paul Jacobsen & David Lan’s [BRAND REDACTED] mobile phone commercial work. And, yes, I just put myself in the company of Mssrs. Malick and Stone. Hank was at home, helping visionaries while struggling with, y’know, gree-een ad hacks. Perhaps the more generous and less self-effacing way to put it is: impressionistic films have a longer leash than, say, 30-second commercials trying to pack in all the new bells and whistles.

However you want to spin it, in the end, the client spent $1.3 million and left the agency within a year26. I spent weeks in Prague, Berlin, Frankfurt, and Prague again, plus a good few weeks hanging out in Hank Corwin’s studio, eating non-Monday sushi and offering up every seventh edit idea that came to me.

And all I got out of it was:

Not sure what happened but the guy’s purple coat was cool.

also beat-up

The bidding war among publishers is furious. Pages have been ripped. Bindings broken.

The guy in the purple coat wasn’t even the protagonist of the commercial, either. Our protagonist was actually a charming 20-something dude from Berlin.

I worked with an extremely talented, impossibly hard-working, entirely idiosyncratic art director named David Lan. He was very good at his job. A man of demanding standards and attention to detail. We had been partners since sort of stumbling into each other during our final year as Advertising majors at BYU. We got each other, for the most part, and made up for each other’s weaknesses.

Not a word.

translation: Old Phones Sucked

How do you credibly explain to a kid who can dictate text messages to Siri and re-order Dr. Squatch deodorant from Alexa that, once upon a time, you had to press the 7 key four times just to conjure up one single letter “s”?

Not a word.

A decade later, my partner Bren and I pitched a similar “hero’s fantastical journey to discovering how all-in-one [PRODUCT REDACTED] is” tv ad to a client who bought it and sent me to Auckland, New Zealand and London for about a month to shoot. The ad never aired. I don’t know if the product ever even….existed.

One of my favorite quotes from my ad days:

The plural of moron is focus group.

I should note that this client was DESPISED. And not just in the stereotypical “Oh, we are so creative and this square client does not get us” way or even the “Clients are sooo annoying way” that would seem pretty obvious. No. This was different. It was on another, far deeper level. Like I said, the agency had been pitching tv commercial concepts for a whole year with nothing to show for it. Always going back to the drawing board. The client was always pivoting, moving the goalposts. Caustic feedback. Lashings. “Yes, sir, may I have another?” The main client was, by every in-agency account, a nightmare at best and an abusive bully/tyrant, also at best. Cold. Harsh. Brutal. Performatively cruel. I had very limited exposure to this guy. But let’s just say that, a year after we shot this video, the client had left us to go abuse another agency. And some months after that, we learned that this guy had suddenly and unexpectedly died. As someone who had worked on the account, I was then on an email chain full of the darkest “humor” I have ever read, just people dancing and spitting and doing all manner of unholy jigs upon this person’s grave. You don’t wanna live your life in such a way that there are long email threads of people taking turns pissing on your life when they find out you’re dead. Eesh.

I couldn’t write “special new brand” without thinking of Stephen Malkmus’ caustic delivery of the lyric “a special new band” at the 1:05 mark of Pavement’s “Cut Your Hair.”

This is the part where I ashamedly tell you how my first commercial ended with the all-time hackiest I Don’t Know How To End This ending ever: “it was all just a dream.” Really. My only excuse is that it was my first commercial. It’s an easy (unfulfilling) way out, used with different degrees of success in Wizard of Oz, The Matrix, Newhart, Dallas, and on and on. So I’m not the first and I won’t be the last, is what I’m saying.

Why Prague? For some obvious and some less-obvious reasons, production costs are lower in other areas than in the United States. The two most expensive shoots of my advertising career were in Prague and Auckland, New Zealand (with Johannesburg being the other option for the latter). I’m not complaining.

I remember one seasoned Creative Director, early in my career, lamenting how they used to be able to expense prostitutes. “The golden age,” I believe he said. By the time I got there, we were asked not to use the minibar.

In the course of our time together (mostly just the working hours…he had his own extracurriculars), it came to light that More Senior Freelancer had been the guy behind one of my favorite ads at the time. It was this HP ad that used The Cure’s “Pictures of You” really well. It wasn’t my favorite because it was Spike Jonze or Michel Gondry-level creativity. It was my favorite because it was more than just tricks and brand coolness. It got to the product while also being visually interesting and emotive. When I first saw it, I thought, “that’s the kind of ad I wanna make.”

I gushed about it. Nate brushed off my compliment with “Oh, that one pissed me off. Didn’t turn out even close to how we drew it up.” One man’s trash….

Years later, somebody at work would mention how “apparently Scarlett Johansson is dating some NYC ad guy” so I googled it and who did I see cavorting on the beach with Black Widow?

Nate, that’s who.

He’d directed Super Bowl ads, won Cannes Lions (the Oscars of the ad world), Clios, Addys, and even has one spot he directed on permanent display at the MoMA in NYC.

Maybe we’re getting to the heart of the real reason I wasn’t all that fond of Frankfurt.

I, for one, couldn’t be more relieved that we’re done with all of the pearl-clutching and self-righteousness around the audacity to DARE make a living with your music. My line is open, people at Apple.

His album (A Grand Don’t Come For Free) with the cheeky song we wanted (Fit But You Know It, which, with 54 million streams, is his most-streamed song) eventually went to #1 on the UK charts, so he did fine without us. There is a small part of me that feels validated that we really wanted this song, which hadn’t become a hit yet.

Not a word.

I dug the little distorted whistle-ish hook that comes in around 0:17. The song has about 4k lifetime streams, so, no, it didn’t exactly hit for us or them.

Cassel had a cool career. Not a huge household name, but a go-to character actor for two pretty amazing directors: John Cassavetes and Wes Anderson.

He even received an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor in 1968 for his role as Chet in Cassettes’ Faces.

Unrelated, he is credited with giving rock guitarist Slash his nickname.

Hank’s IMDB page is pretty wild. His first editing job was as an “additional editor” on the Oscar-winning 1991 Oliver Stone film JFK, which turned into a main editor gig in 1994 for Stone’s controversial Natural Born Killers. Then:

1995: Nixon (Stone)

1997: U-Turn (Stone)

1998: The Horse Whisperer (Robert Redford)

1999: Snow Falling On Cedars (Scott Hicks)

2000: The Legend of Bagger Vance (Redford)

2005: The New World (Terrence Malick)

2008: What Just Happened (Barry Levinson)

2011: The Tree of Life (Malick)

2013: Jimi All Is By My Side (John Ridley)

2014: After The Fall (Saar Klein)

2015: The Big Short (Adam McKay)

2017: Song By Song (Malick)

2018: Vice (McKay)

2021: Don’t Look Up (McKay)

Not my fault.